The Helix consensus algorithm and the Orbs architecture built around it are sparking interest from blockchain stakeholders around the world. Our team holds tech sessions with interested parties to help spread the knowledge about the protocol and encourage companies to adopt and build upon it.

I decided to document the latest AMA session we had with GroundX, the blockchain subsidiary of Kakao in South Korea. Their questions were very interesting and are probably relevant to others as well. Since we try to promote a transparent culture in Orbs as much as possible, publishing these sessions from time to time is important.

If you and your company are interested in having such a tech session with the Orbs tech team, don’t hesitate to contact us at hello@orbs.com.

···

The default fee model for virtual chains — inherent and intelligent shards, i.e. isolated blockchains for each individual dApp on the Orbs network—is based on a monthly subscription (very similar to renting resources from a cloud provider like AWS). The cost of the virtual chain is pegged to the cost of infrastructure. In other words, it is proportional to the amount of resources it guarantees and reserves on the nodes in the network (higher transaction throughput and more storage naturally increase the cost).

Anyone can purchase a virtual chain from the network. Payment for a subscription is made to a management smart contract. The subscription smart contract is holding the fees until the end of the billing period, and then distributes them to the network nodes who participated in operating the virtual chain.

If an app wants a dedicated virtual chain, the app developer is welcome to pay the subscription fee and deploy a virtual chain for this app. This doesn’t have to be a centralized entity though — a DAO can also pay the subscription fee since payment is done directly to a smart contract. The model is very flexible. A collection of stakeholders can join together and fund the subscription as a group, each sending some amount of tokens every month.

The network doesn’t really care who funds the subscription. The virtual chain will remain live as long as the subscription is paid (a required total of ORBS tokens is transferred to the management contract according to the desired resource tier).

A slightly more advanced mechanism of a programmable fee model also exists on Orbs and allows an app to create a smart contract that funds its virtual chain according to any custom rule it desires (for example — taking a cut out of users’ transactions). We’ll discuss this model in more detail in a separate future post.

···

Helix separates the ordering and validation phases of the consensus. The two phases actually result in two different blocks committed to the blockchain: The first is a transactions block (which lists the transactions and sets their order, this is the result of the ordering phase). The second is a results block (which lists which transactions are valid and shows their output state diff, this is the result of the validation/execution phase).

There’s an important distinction when working this way. When a transaction is committed to a transactions block, it’s not approved yet. Only after the results block is committed we can know whether the transaction is approved or not and what are its outputs. One of the features enabled by this approach is opaque transactions — meaning transactions that are encrypted by end users without the leader’s ability to examine their content before committing them to a block. The transactions in the transactions block are decrypted only after consensus over the block (utilizing threshold encryption).

The specifications for execution of transactions and creation of the results block are part of Helix execution service. We are working on a new paper which will demonstrate how to scale transaction execution in Helix in a very substantial factor.

It may seem that committing transactions to a transactions block before they are executed might incur waste (if the number of invalid transactions is high). Our measurements show that for most apps, the optimistic assumption that most transactions are valid provides the better tradeoff (attacks are an edge case where the responsible parties can be punished). This optimization guarantees fairness in ordering since nodes cannot see the transaction content until it has been committed. Since opaque transactions is an optional feature, a virtual chain can also decide to opt out (and avoid encryption on transactions). This will allow transactions to be validated before they are committed to the transactions block.

···

To answer this question, we must first understand who can deploy smart contracts on Orbs. Smart contracts are always deployed in the context of a virtual chain. This is an isolated context because different virtual chains use different resources and do not affect each other. For example, regarding storage, every virtual chain has its own separate storage which is billed separately in monthly cycles according to the relevant subscription tier (for example, 10GB storage costs X ORBS tokens, 100GB costs Y tokens, etc.).

When a virtual chain is created, its creator can limit who can deploy new smart contracts to it. For virtual chains that are dedicated to running off a specific app, it makes sense to limit smart contract deployment to the developer of the app only. This gives the app developer full control over which contracts run on the virtual chain they are subsidizing. These contracts are free to incorporate logic that rejects executions that are considered spam and consume too much resources.

This business model has been proven for consumer apps on traditional cloud providers like AWS, where the app developer deploys the backend code to their virtual machines and is free to reject requests by users if those are considered spam. In most consumer cases, the app developer will subsidize infrastructure costs to all users ignoring the nuance of much resources each user consumed. Consider a chat messenger — users can send images to their friends, but it doesn’t matter if a user sends 10 images or 100 images. Users will only be blocked if they are marked as spam (sending over 10,000 images in one day for example).

There are some cases where the creator of a virtual chain requires more control over which transactions are executed and how. This is the case for example when an app developer wants to fund the virtual chain subscription from user transactions. This is possible in Orbs through programmable fee models.

Consider an Airbnb app where users pay a contract a relatively large amount to rent a vacation property. The app developer can decide to allocate 1% of the amount transferred as a fee to help fund infrastructure costs. Since this logic is custom per app and its unique business use case, it is implemented as an auxiliary smart contract on the virtual chain which runs before a transaction is approved. We’ll cover this feature in more detail in a separate post.

···

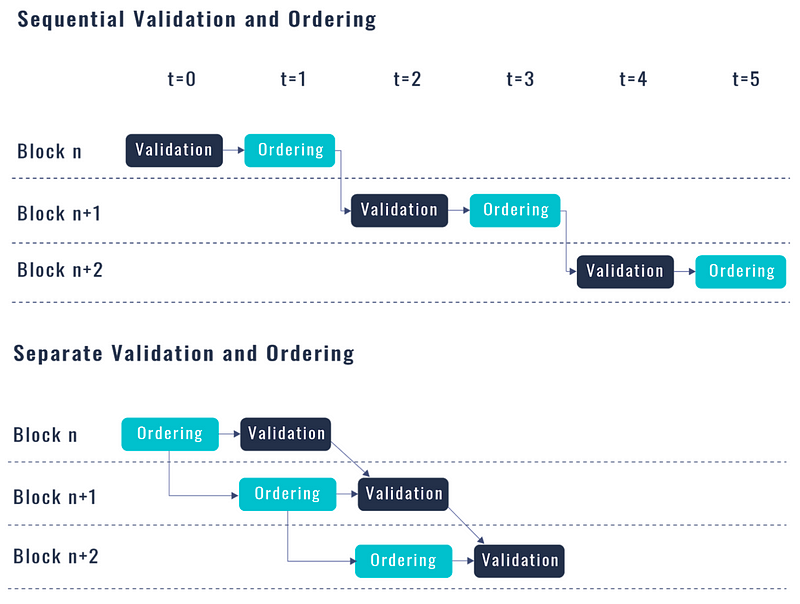

Most blockchain implementations perform the ordering and validation immediately one after the other in sequence as a single step. Transactions are first ordered, and then immediately executed and validated (removing the invalid ones).

Orbs allows the ordering and validation phases to be processed independently and have independent consensus rounds (possibly with a different committee of nodes for each!). Nevertheless, transactions cannot be considered confirmed until both phases have completed. This means that this separation has no substantial impact over transaction confirmation time (latency). This is because the total amount of time needed to process both phases immediately one after the other is roughly the same.

The performance benefit provided by this separation comes from pipelining. We can parallelize ordering and validation, but on different blocks. For example, when block #100 is ordered, block #99 can be validated in parallel. In the next step, when block #100 finally goes through validation, block #101 can be ordered in parallel. The pipeline mechanism improves the transaction throughput of the network.

You can see an example of the pipeline in this diagram:

···

Let’s use some numbers to give this question context. Let’s assume there are a total of 1000 nodes in the network. We have a single virtual chain with a redundancy level set at 21 (this is configurable per virtual chain). This means that for every consensus round on this virtual chain, 21 nodes will participate.

For every block, a different committee of 21 nodes is chosen randomly among the 1000 nodes of the network (to be exact, if we go into the nuance of separate ordering and validation rounds, each block actually involves two different committees). The randomization process — which we dub randomized proof-of-stake (rPoS) — works by shuffling the list of 1000 nodes and taking the first 21 nodes of the result. In addition, the first among the 21 is designated as the leader (or the proposer as defined in the question). If this leader doesn’t propose a block in time, the responsibility for being leader shifts to the next node in line.

The randomization process isn’t purely random but a weighted random — it incorporates the node reputation score when randomly sorting the list. This means that a node with twice as much reputation is likely to appear in twice as many committees, and be chosen as leader twice as often.

One of the important characteristics of the random sort is unpredictability and resistance to manipulation. We wouldn’t want nodes altering the block content somehow to increase the chances of their friends appearing in the next committee. This is achieved once again using threshold encryption. The interesting property of threshold encryption is that a value can only be uncovered once the threshold of signers is met. If the random seed for the next committee is generated from the previous block only after threshold, none of the nodes can predict the result on their own.

···

Every virtual chain on Orbs is independent, maintains its own consensus processes, and keeps its own chain of blocks. This means that there’s no single main chain where the virtual chains need to synchronize. The sharding is inherent to the system and different virtual chains can be processed completely in parallel using different resources (different machines for example).

Orbs does have a single management chain, but this chain isn’t involved in the critical consensus path of independent virtual chains (it is not involved when they close blocks). The management chain is used to host smart contracts that manage the Orbs network in general (for example, the smart contract which holds the official list of active federation members). Whenever the network wants to change this global property, like adding a new federation member, a transaction needs to be sent to this smart contract.

Another example use case for the management chain is voting on protocol modifications. When the protocol is updated, federation members are required to vote to accept this change. This vote is also orchestrated by a smart contact on the management chain.

One drawback of having completely independent virtual chains is that transactions across virtual chains are expensive (since both chains have to synchronize over the special cross-chain transaction). We feel that this is the correct tradeoff since contracts on different virtual chains aren’t supposed to be related nor manipulate the same state.

···

SLA in Orbs is guaranteed per virtual chain. The two main properties of a virtual chain are 1) transaction throughput and 2) storage. Naturally, if a virtual chain requires more resources, its subscription will be more expensive. The dApp’s devs can upgrade.

Transaction throughput is measured in compute units per second. For simplicity, assume that the simplest useful smart contract requires one compute unit. If a smart contract is twice as complicated, it will require two compute units. Since execution fees on Orbs are low, the granularity of execution doesn’t need to be on the opcode level (like on Ethereum). The model is closer to the one used by traditional cloud providers like AWS (CPU minutes).

This means that the virtual chain doesn’t care which contracts run in it and how complicated they are. The virtual chain guarantees a certain level of compute units per second and it is up to the app developer to allocate this resource according to their app’s needs.

Nodes are incentivized to help operate virtual chains by the subscription fees paid to them. When a node offers to participate in the operation of a virtual chain, it is required to commit enough hardware resource to withstand the performance requirements of the virtual chain. If the node is unable to fulfill this commitment (by allocating less hardware than needed for example), its reputation score will be decreased as this is observed by the other nodes.

Node reputation has a direct relationship to its portion of the fees. A node with a low reputation score will not be compensated for its services like a node with a high reputation. In addition, when node reputation is low, its level of participation in general will decrease as it will participate in less committees and be designated as leader less times.

···

If the two apps are deploying their smart contracts on the same virtual chain, they will share blockchain state and will be able to easily implement a token sharing mechanism.

If the two apps are deployed on separate virtual chains, each will maintain its own isolated blockchain state. This should be the case when the apps don’t need to share tokens, or at least this isn’t common.

It is still possible for two apps on separate virtual chains to communicate. This is performed via a special mechanism called cross-chain contracts. These special transactions are slower and more expensive since they require synchronization by two independent consensus processes.

···

The assignment of resources is done through the protocol in a decentralized manner. The process has to be decentralized because having a single entity in charge with managing the pool would skew the decentralized nature of the network. When the protocol dictates how resources are assigned, the interesting question becomes — how can we enforce that the various nodes are behaving according to the protocol?

The core mechanism for enforcing node compliance to the protocol is reputation. A node’s reputation score is depended (among other things) on how well the node fulfills the commitments it has taken upon itself by participating. Many of these parameters can be measured in a deterministic way under consensus.

Consider for example the following protocol rule — nodes must adopt and upgrade to new approved codebase versions as early as possible. How can this be measured? Whenever a node is a leader and proposes a block, it embeds the protocol version inside the block data. It is difficult to lie with this version number since claiming to support a newer version of the protocol than you actually do will cause other nodes to communicate with you using protocol messages you won’t necessarily understand. Since leaders change frequently, it’s easy to measure how much time (how many blocks) it has taken every node to upgrade.

Another example — nodes are expected to allocate enough compute resources to handle the required load for participating in the protocol. How can this be measured? Suppose a node allocates half the resources compared to everybody else, for example by renting a very cheap machine on AWS. If honest nodes can participate in a committee every X seconds, this node will only be able to participate every 2X due to its limited resources and inability to keep up and validate transactions fast enough. When the list of validators is analyzed in closed blocks or the number of times the node has fulfilled its leader responsibility successfully, it will be evident that the node is not keeping up with the others.

···

I assume this question refers to the secret bearing network feature of Orbs. This mechanism allows smart contracts over Orbs, which are decentralized entities, to store private keys. This functionality isn’t straightforward because traditional smart contracts are unable to retain secrets. This is due to the fact their code is open and can be fully executed and verified by any node desiring to do so.

Why is this mechanism useful? It can be used to allow a smart contract to access a protected resource, such as an Ethereum account. Imagine a smart contract that can sign a secure Ethereum transaction. This mechanism can also be used to allow end users to backup their private keys on a smart contract over the network and defines decentralized means of recovering it.

The mechanism is secure and relies on a well known cryptographic primitive called threshold encryption. Using this primitive, every node in the network holds a single share from a distributed secret. Only when enough shares are used for some secure operation, like a signature, the combined signature emerges. This allows the entire network to sign something as a group without allowing any of the nodes to retain full knowledge equivalent to the combined underlying private key.

···

As usual the answer depends on the use case. Buying stickers with microtransactions on a messenger app is different from holding your life savings in a secure account. The question isn’t only what’s optimal for end users, but may also have compliance and regulatory implications.

Unlike many blockchains which rely on fixed quorum sizes, Orbs allows the committee size to be configurable per virtual chain. The creator of the virtual chain is free to make this choice as it influences performance (larger committees — the consensus will be slower), fees (larger committees — the subscription is more expensive since more nodes need to participate) and security (larger committees — the chain is more secure). This property can even be changed on a live virtual chain and will take effect from the following blocks.

Popular blockchains focusing on consumer applications, like Stellar and EOS, are using quorum sizes of about two dozen nodes. It seems that this number provides a good tradeoff for consumer apps that you don’t use to hold your life savings.

Another interesting aspect to understand is that security doesn’t only come from increasing the committee size. Orbs provides significant security benefits as the total number of nodes in the network increases. A committee of 21 nodes on a network with 1000 nodes is more secure than a committee of 21 nodes on a network with 100 nodes. Since performance is mostly proportional to committee size, this encourages as many nodes as possible to join Orbs and make the overall network more secure without hurting performance.

Why is that? First, committees are random and cannot be predicted in advance. Suppose an adversary has successfully taken control of 14 nodes. It now has a definite majority in all committees containing these 14 nodes. The adversary can wait patiently until such a committee is randomly selected and then attack. It’s true that this will take more time as the network grows, but the effect isn’t significant since the block rate is very high. By increasing the number of consensus rounds to two (over the same block), we can make the system significantly more secure. Let’s say that in the first committee the adversary has control (the 14 nodes were randomly chosen) and now the adversary needs to decide whether to attack or not. The chances that the same 14 node group will be chosen randomly for the second committee are slim. If the adversary will attack, they will most likely be caught and punished.

···

Yes, since the project is relatively young, the majority of contributions is still performed by the core team working at Orbs Ltd. Nevertheless, Orbs is a decentralized and open source project. Anyone can contribute to the project. The core team is providing leadership, but it’s a priority for the project to add as many additional contributors as possible.

The first line of external contributors will most likely be engineers working for our design partners. Currently, most of these collaborations take place over auxiliary projects (such as the client SDK) and not yet at the node core. This is likely to change as Orbs matures towards a first secure version in production.

As the project grows, we’ve made it a clear goal to increase the developer community involved in the project. The true power of decentralized projects lies in the community they form around them.

···

We first need to consider what is the main thing being developed in Orbs — the specification for a decentralized protocol. This is the most important deliverable which we are focusing our efforts on. In the initial stages, this involves significant research and product positioning (which are published among our white papers). The protocol specification is also being properly documented and found in a dedicated Github repository.

The first reference implementation for the Orbs alpha is written in Typescript. Typescript is a great language for rapid prototyping and showcasing our ideas quickly in a way that a large community can understand them (JavaScript currently has the largest developer ecosystem in the world). Fine tuning performance was not the main focus of the alpha.

We are encouraging a polyglot environment where reference implementations exist in various programming languages. As long as all implementations conform to the protocol, the more implementations found in the Orbs community the stronger the project becomes.

The core team is currently in the process of adding another language for a reference implementation of the next version of the protocol. This version is more focused on performance and security and will be based on a language different from Typescript. One of our leading candidates is Go. We’ve already outlined our team workflow for Go in a guest post on freeCodeCamp — you can read it here.

···

The purpose of the alpha is to start integrations as early as possible with real customers so development can work side by side with real business use cases. Orbs has always differentiated itself as being requirements driven — meaning our main focus is building a practical production solution that real world consumer apps can actually build decentralized businesses with.

In order to design Orbs according to real use cases, the Orbs project has collected a series of design partners from different product domains. In the alpha stage, which is released on Q2 2018, these real businesses start sending real traffic to Orbs nodes. We call this process mirroring.

The idea behind mirroring is sending traffic to Orbs in parallel to any current production solution these apps are currently using. Some of these apps, like PumaPay, are still relying on centralized systems and are slowly starting to decentralize them over blockchain. Mirroring allows to do this process gradually as the traffic from the centralized systems is forwarded to Orbs as well. Some of these apps, like Kin, are relying on other blockchain infrastructure solutions like Stellar. Mirroring allows to compare the performance and stability over Orbs to the performance and stability over these solutions.

The main idea behind mirroring is to make the migration process to Orbs risk-free. Infrastructure migrations are probably the biggest barrier for adoption of new technology. In addition, working on real traffic allows the Orbs project to develop faster and improve itself based on real world scenarios.

The next version being developed by the core team is dubbed V1 — the first production version that will be available as public main net. The version has already started development. Its specification is already being documented on Github. We expect this version to be ready by the end of the year.

We use cookies to ensure that we give you the best experience on our website. By continuing to use our site, you accept our cookie policy.