Israeli Networking Day (IND) is an annual event bringing together researchers and engineers from both academia and industry to discuss recent research activity in the field of networking. The 2018 IND, jointly organized by Orbs and VMware, was held on May 24th, and included 24 talks on recently published papers or ongoing works.

I presented Helix, the Orbs consensus protocol. The following is a detailed summary of the talk, and can be viewed as a simple introductory overview of HELIX and of consensus protocols in general. Towards the end of the post I focus on one of the innovations in HELIX, namely the way it restricts ordering manipulations.

The presentation should be accessible to anybody in the tech world, with virtually no prior knowledge required.

Orbs is building a blockchain designed for the needs of apps with large numbers of users moving their activity over to the blockchain. For various reasons, existing solutions do not fit these apps’ needs, and our challenge at Orbs is to design a blockchain that does.

Blockchain means different things to different people. In this presentation, I consider it from a theoretical perspective, viewing blockchain simply as a data structure. It is comprised of an ordered chain of blocks, each block containing an ordered list of transactions. This data structure is constructed continuously, as new blocks are periodically appended to the end of the blockchain.

Transactions are never removed from the blockchain. An important advantage of a blockchain over other data structures is that it has the properties of being stable and untamperable. By this, I mean that it should be impossible to make any changes in the order of transactions once they have been appended to the blockchain (In the Helix Consensus Algorithm, we make it essentially impossible to make changes in the order of transactions even before they are appended to the blockchain — more on that below).

These properties are mainly attributed to the distributed and decentralized character of the protocol constructing the blockchain, usually referred to as the consensus protocol.

Let’s take a few moments to understand what exactly ‘distributed’ and ‘decentralized’ mean in our context, as these concepts are crucial to the understanding difficulties and opportunities in the blockchain world. A ‘decentralized’ system is one in which no single authority has control over the system; the power lies with several different authorities. In the blockchain world, control is typically given to the nodes (the servers in the network constructing the blockchain) participating in the consensus protocol.

Controlling a system, or a protocol, should be understood in a broad sense: Starting from the decision on which players are allowed to participate, and going through defining the role of each player, the desired output of the protocol itself, etc..

By saying that blockchains are ‘distributed,’ I mean that the consensus protocol is run by a number of nodes who interact and decide together — usually based on majority — on the next block to be appended to the chain. Moreover, nodes keep a local copy of the blockchain (i.e., of the ordered list). This way, both the construction and storage is done in a decentralized manner, with no trusted party coordinating the decisions of the nodes. This combination assures that both a priori (by decentralized distributed construction) and a posteriori (decentralized distributed storage), performing manipulations to the order of transactions requires the agreement of a majority of the nodes in the network.

Image by Marina Rudinsky

The qualities of decentralization and distribution come at a cost. When transactions are of value to the nodes of the network, as is usually the case, different nodes usually have different interests regarding the order of these transactions. Each node typically wishes to prioritize some transactions over others. A major challenge in designing a blockchain consensus protocol is agreeing to a specific order. A first step towards a solution is to decide what is considered a good order.

For us at Orbs, we decided that a ‘good order’ is based on a ‘fair share’ approach: Each node’s transactions should be represented in each block in proportion to this node’s representation among all issued transactions. To put it another way, if for example a node issues 14% of the transactions in the network, then each block should include roughly 14% of this node’s transactions.

To achieve this goal, we came up with the concept of a fair ordering protocol — a protocol in which all issued transactions have equal probability of getting included as the next transaction in the ordered list (i.e., in the blockchain).

Such a protocol is free of ordering manipulations attempted by the nodes constructing the blockchain. With Helix, we designed a fair ordering protocol by using randomness to obtain a random ordering of transactions. Indeed, random is fair: a random order is, by definition, completely free of manipulations.

Before we drill down and explain Helix in detail, let me point that — to the best of our knowledge at Orbs — no other consensus protocol is fair in this sense. Usually, the order of transactions in each block is completely determined by one of the nodes in the network (consider Bitcoin’s miners for example). While this prevents other protocols from neither being distributed nor decentralized (these properties are achieved via other aspects of the protocol), it does render them completely unfair in the above definition.

In order to explain how we obtain this in Helix, I will present a high-level sketch of our network and of the other parts in our consensus protocol. For those of you who are more familiar with these concepts, let me briefly say that what we do in Helix is to use a Verifiable Random Function (VRF) to generate an ordering of the transactions. To do this properly, we have to overcome some difficulties imposed by the asynchronous nature of the system, which we do by incorporating techniques from the field of Statistical Hypothesis Testing (SHT).

For those of you less familiar with these ideas, don’t worry! I explain all in detail in the next section.

Let me begin by clarifying that Helix is an ordering protocol: the execution of the ordered transactions is done using another Execution protocol (to be published soon), which handles all kinds of invalid transactions and other execution related difficulties. To keep this post more concise, I only focus on the ordering with the layer of the nodes: In particular, I ignore the question of validity of transactions, as well as user-node interaction.

Quickly reviewing the Orbs protocol, we have nodes (corresponding to the different applications in the Orbs Federation) which issue transactions. These nodes forward their transactions to all other nodes in the network, which results in each node holding a pool of pending transactions. All nodes participate in an agreement protocol, through which they construct the next block, i.e., decide on a subset of pending transactions and order them in a block. This block is then appended to the blockchain and the transactions it contains are removed from the nodes’ pools of pending transactions.

Now I will turn your attention to an important detail: the pools of transactions differ between different nodes.

This is for two reasons. First, network latency. We cannot expect data to reach all nodes at exactly the same time. This is true in centralized systems, even more so in a decentralized setting.

Secondly, in distributed protocols, no two nodes are in the same phase of the protocol at a given time. Consider the simplest example: a single node in the Orbs network issuing a transaction. One cannot avoid the fact that the issuer node ‘knows’ about this transaction before all other nodes. There are many more examples. In our context, the difference between pools of transactions causes a difficulty in constructing a random order of transactions.

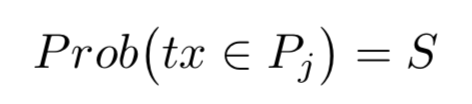

Such problems have many solutions in the field of asynchronous networks. Our focus here is guaranteeing a random ordering of the block despite this difference. To prove mathematical claims, we model this difference by declaring that any transaction which was issued by node i is in a pool Pj of another user j with probability S. We think of S as a parameter of the network, and it is assumed to be quite high (say 0.9 or even 0.95).

In each term, a leader is elected among the participating nodes to be the one constructing the block for this term, choosing transaction from its pool of pending transactions. The leader then proposes the block to the other nodes for them to perform a validation procedure: each node decides whether to accept or reject the proposed block. The fundamental issue here is by what criteria nodes should require to accept or reject the block? Or, how should we formulate this criteria to ensure fairness is guaranteed?

Recall that a fair ordering protocol is a random one, that is, a protocol in which each issued transaction has an equal probability of getting included in the next block. Notice that if the leader randomly selects an ordered subset of transaction from its pool, the fairness property is duly guaranteed. We thus wish to formulate a validation condition which will make sure the proposed block was indeed constructed ‘randomly.’ If a large enough fraction of nodes accept the block, then this block is appended to the blockchain and the next term begins.

There is a tradeoff to notice here: If we impose strict validation criteria, we may guarantee randomness, but on the other hand many blocks might be rejected even though they were constructed ‘randomly’. This would slow down the protocol. The choice we made regarding this tradeoff is in favor of the liveness of the protocol: We restricted ourselves to validation conditions which accept randomly constructed blocks with overwhelming probability. Under this constraint, we tried to maximize the guaranteed randomness of each block.

Before we proceed with the protocol, let me draw your attention to an important aspect of decentralized reasoning. Notice that in the above description we do not trust the leader and make its proposed block go through a validation procedure, made by other nodes. However, there is no essential difference between the leader and the nodes performing the validation. The only difference is that on this specific term, the leader node was elected. Why then should we trust the nodes to perform the validation anymore than we trust the leader to construct an honest block in the first place?

The answer is simpler: In a decentralized setting, we cannot and do not trust any single node. We must always assume that some (small) fraction among the nodes in the system are malicious and do not comply with the protocol. However, we do trust the system as a whole, which in practice says that we trust a majority of the nodes in the system to act honestly.

This is the fundamental distinction we make in consensus protocols, and is the source of many interesting and beautiful ideas which makes this field so interesting and full of potential.

To make things even more complicated (and more interesting), in many scenarios in the blockchain world, including our use case at Orbs, we cannot even assume that the majority of nodes would act exactly according to protocol. Rather, we should expect them to pursue their own interests. The protocol must be designed in such a way that would take this into account. But this is a bit out of scope for this post.

It is difficult to know whether or not an ordered list of transactions was picked randomly. In a truly random construction, any two specific orders are equally likely to appear. How can we ensure the leader doesn’t choose its block in a selfish and manipulative way, relying on the fact the other nodes won’t be able to tell the difference?

This problem was considered in the work on Verifiable Random Functions (VRF) of Micali, Rabin and Salil. In a nutshell, a VRF gives you a method to construct a random function (in our case, a function which outputs a random order of transactions) in a way which is verifiable by other nodes in the network. The standard implementation of a VRF in our scenario is by using cryptographic hash functions. The idea is the following:

Apply a Hash function H to each of the transactions in your pool, and order the transaction according to their hash value.

Then, include the first b transactions of your ordered pool in the proposed block (the parameter b stands for the maximal number of transactions in a block. We think of it as being around 1/10 the size of a pool). The hash function induces a random order on the transactions in the pool. All nodes can then verify the leader did not manipulate the ordering — they simply apply the same hash function to their own pool, and compare the two block versions: the local block version, and the version proposed by the leader.

The naive thing to do next is to ask each validator to accept if and only if the versions are exactly the same. However, due to the differences between different pools, such an equality between the blocks would never hold.

The right approach would be to accept whenever the two block versions are similar. More precisely, take the pools similarity parameter S, induce from it a block similarity parameter 0<S’<1, and accept if and only if the intersection between the two block versions is of size at least b (we assume b=|B|, the size of the block B). Straightforward considerations readily imply that S’ should be a bit smaller than S, which in turn is smaller than 1, and so any validation condition would have to allow the leader some degree of freedom in its block construction.

While this approach is supposed to work in practice, we found it not satisfying a required level of accuracy, and moreover difficult to derive theoretical guarantees for its performance. The theoretical difficulties originated from the fact that in order to make the idea above precise, some conditional probabilities needs to be calculated. To overcome this, we took a different approach, and the first step was to analyse the adversarial behaviour we are trying to restrict.

Our work on these conditional probabilities turned a spotlight to what we call the threshold hash value. It is the hash value of the highest valued transaction, when considering the block ordered by the hash ordering. since there are b transactions in a block, this is the value of the b-th transaction in the proposed block.

Consider a leader who wishes to promote a fraction of transactions from its pool over other transactions. As I mentioned above, the pool differences would force any validation condition to allow some degree of freedom to the leader in choosing which transactions to include. By using the hash ordering, and since all nodes in the network use the same hash function, they can duly verify that the transactions in the block are indeed ordered by their hash value, so a transaction with higher value must appear after transactions with lower hash value.

This leaves the leader with only one way to manipulate the block construction: Instead of including strictly the first b transactions, the leader can take some of these out of the block and include some other transactions with higher hash value. It can then hope that the other nodes would ‘believe’ that the difference between the leader’s block and their own version is due to the pool differences — and not due to the leader’s manipulations.

What would be the effect of such manipulation? The most apparent effect is that the threshold would be higher than what it should have been in an honest construction. As this value is absolute (it is a numerical value), and is made public once the block of this term is proposed by the leader, this value can be exploited exactly for our needs, using the concept of Statistical Hypothesis Testing.

Briefly, in a SHT setting, a player makes a hypothesis, and a verifier is asked to decide whether or not this hypothesis is true. The verifier does not have the complete knowledge required to make this decision. Instead, it is assumed that the verifier has access to a partial sample of the relevant data. As a consequence, it cannot decide with certainty whether or not the hypothesis is true or false. It is thus required to decide how probable it is that the statement is true. The theory of STH is the theory of the statistical tools which help the verifier reach its decision.

In Helix, one can observe that an honest leader makes the following statement: “the block I proposed contains all transactions from my pool which lie below the threshold.” Since the threshold is known to all other nodes, they can check how probable it is that this statement is true.

They do so in the following way: Each transaction in a pool is assumed to lie in the leader’s pool with probability S. For any transaction with hash value lower than the threshold, this transaction should lie in the block proposed by the leader (with probability 1).

Thus, any node can check how many transactions from its own pool, which have a hash value below the threshold, do not appear in the proposed block. If there are too many such transactions, it rejects the block. Otherwise it accepts. While this method sounds very similar to the one described in the previous section (with the S‘ parameter), it achieves much better results in terms of fairness, and these results can moreover be proven by simple mathematical tools (mainly concentration bounds such as Hoeffding and Chernoff inequalities).

The STH approach achieves close to perfect randomness in block construction. In other words, even a small number of ‘illegal’ transactions included in a block may cause it to be rejected by most users. Of course, how small exactly depends on the network parameter S, but even for relatively low values of S we achieve very good results.

The analysis is like so. A leader knows what the validation condition is, and can see how many transactions lie below any potential threshold hash value. This number is a very good approximation to the number of transactions which lie below this potential threshold in any other pool. The leader can now estimate the probability of any potential block to pass validation — based on this potential block’s threshold value.

Our analysis, presented in the graph below (taken from the Helix white paper) shows that for S=0.8, insuring 70% chance of passing validation limits the threshold to have a mere 1.12b transactions below it — both in theory (represented by the blue Chernoff bound) and in practice (represented by our simulations in red). Considering the fact that in a completely honest block this number is exactly b, one can conclude there is very little freedom for the leader to manipulate the order of the next block. Even this freedom is further restricted in Helix by using other tools which were left out of scope, such as encrypting transactions and obfuscating the issuer of each transaction.

With these tools incorporated, Helix achieves close to 100% randomness, and fairness, in each constructed block.

We use cookies to ensure that we give you the best experience on our website. By continuing to use our site, you accept our cookie policy.