The Orbs Liquidity Nexus protocol introduces CeFi liquidity to DeFi.

Now, take any DEX, whether it’s SushiSwap or PancakeSwap, and choose a popular pool like ETH/USDC or BNB/BUSD.

The CeFi capital provides the stable side — USDC or BUSD. The DeFi capital provides the crypto side — ETH or BNB. Now, let them farm together.

Part 1 of this series is published here (read it first).

···

Most popular DEXes are similar in concept to Uniswap and rely on the same risk/reward model. Some examples include SushiSwap, 1inch and PancakeSwap. To understand how their incentives work, digging into the Uniswap model is probably enough.

Let’s assume we are providing liquidity on a ETH/USDC pool.

The classic Uniswap incentives model for liquidity providers is based on 3 main parts:

No. Since we have 2 main rewards and 1 main risk, it all depends on how they balance together. There are multiple factors at play here, like external market prices, how long the liquidity provider spent in the pool, the swap volume in the pool, total liquidity and so forth. Let’s go over some of them quickly:

Generally speaking, the popular farming pairs like ETH/USDC are usually profitable for liquidity providers. Why? Because if they weren’t, there would be no liquidity in them.

We mentioned that IL stems from price change between the two tokens in the pair. In our ETH/USDC example, this happens when ETH goes up or down in price compared to USDC.

How would a liquidity provider experience IL?

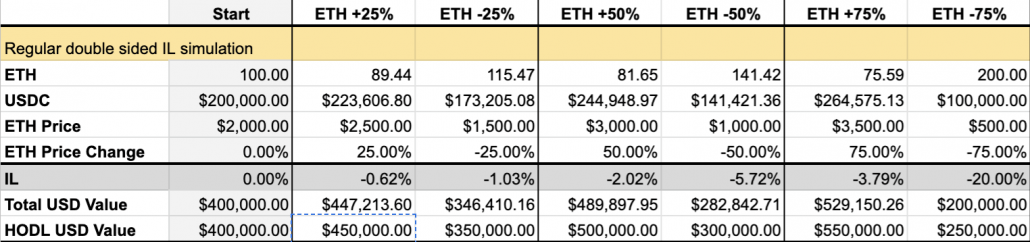

Let’s say that on day 1, ETH price is $2000, and the LP adds 100 ETH and 200,000 USDC (adding liquidity must be balanced). On day 30, when the LP removes liquidity, ETH price is higher and is now $2500. When the LP exits, they would not receive their original 100 ETH and 200,000 USDC back, instead they will receive 89.44 ETH and 223,606.80 USDC.

Is this good or bad? Since price of ETH moved, we know that it must be bad because we have IL. Let’s see how bad exactly:

The total USD value on exit (89.44 ETH and 223,606.80 USDC with ETH at $2500) is $447,213.60. If the LP had never participated in the pool, and kept their original 100 ETH and 200,000 USDC outside, the total USD value of their holdings would have been $450,000.00 (100 ETH and 200,000 USDC with ETH at $2500). This means the LP lost $2,786 which is about 0.62%.

Is this a bad deal? Usually no, assuming swap fees and rewards earn much more than this 0.62% loss.

The following table will help us explore IL as ETH price moves in various amounts (+25%, -25%, +50%, -50%, +75%, -75%):

The concept we’re investigating in this series of posts is sourcing liquidity for ETH/USDC farming from two different parties — one party that provides the ETH and the other party that provides the USDC.

For discussion sake, let’s assume there are no swap fees, no farming rewards but ETH price changes — so we just have IL. How can we split IL between the two parties?

In our previous post, we’ve seen that the different parties have different goals, so the risk does not necessarily have to be divided equally. The exciting parts of the Liquidity Nexus protocol actually come when things are asymmetric.

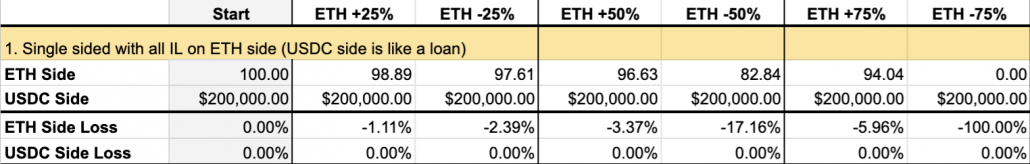

Let’s try to make things completely asymmetric and make the ETH side responsible for all IL. This can make sense because DeFi players providing ETH can be offered higher portion of the rewards (higher APY) in exchange of taking more of the crypto volatility risk. CeFi players providing the USDC will compromise on lower rewards (lower APY), particularly if their exposure to crypto volatility is limited.

How would that work in practice? Let’s go back to the numerical example from before. On day 1, ETH price is $2000. Side A supplies 100 ETH and Side B supplies 200,000 USDC. On day 30, when the sides want to remove liquidity, ETH price is higher and is now $2500. When the LP tokens are burned, instead of the original 100 ETH and 200,000 USDC, we now have 89.44 ETH and 223,606.80 USDC.

If Side B does not suffer any IL, the fact that ETH price moved to $2500 should not affect it at all. Since our example only has IL and no rewards and no fees, Side B should withdraw exactly the 200,000 USDC it originally deposited. Since we have 223,606.80 USDC available on exit, after returning the 200,000, we have 23,606.80 USDC remaining. We will naturally use this remainder to compensate Side A as much as possible.

Let’s run the numbers and compare to the table from before:

We can see that the IL for Side A is roughly doubled, which makes sense because only one side is taking on all of it. A different and interesting way of looking at this strategy is saying that Side B doesn’t actually really farm. Instead, Side B is giving a loan of USDC to Side A. But this loan is much more efficient than those available on Compound and Aave. The efficiency stems from the fact that the collateral doesn’t just sit there, it is actively farming and generating high yield. Since contracts will implement this behavior, we can allow Side B to reclaim their USDC at any time by automatically unwinding the LP position when they do so. In other words, even if the collateral is farming, there isn’t much added risk.

Another interesting edge condition worth mentioning is what happens if ETH value drops by 75%. It is true that this is a bit extreme, but exploring the extremes helps us fine-tune the economics. In this case, you can see that Side A, that provided the ETH, loses all of its capital.

Does this make sense? There’s no right or wrong answer. It may be justified by the following:

Nevertheless, you may not like this behavior, so we can tweak the algorithm slightly to avoid it and divide IL in a different way:

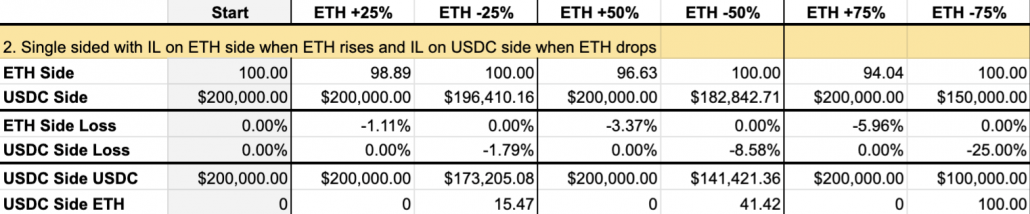

Here’s another interesting alternative. Looking at the table of strategy 1, we can see that when ETH goes up, the model behaves nicely. The edge conditions come when ETH starts dropping, particularly to extremes of over 75%.

What if the USDC side shares some of the IL in this case? This wouldn’t give it complete protection against crypto volatility, but will be able to protect the other side from serious losses.

How would that work? If ETH goes up, we behave like in strategy 1. So let’s examine a case where ETH goes down with numbers in our previous example. On day 30, this time, when the sides want to remove liquidity, ETH price is lower and is now $1500. When the LP tokens are burned, instead of the original 100 ETH and 200,000 USDC, we instead have 115.47 ETH and 173,205.08 USDC.

Protecting Side A to the fullest in this case would maintain its principal of 100 ETH. This would leave extra 15.47 ETH which we can use to compensate Side B as it would incur a small loss. It’s an interesting question whether we want to keep this 15.47 ETH as ETH or swap it to USDC. On one hand, Side B prefers to work in USDC, so swapping makes sense. On the other hand, if ETH just dropped in price, this might be a bad time to sell. Let’s leave this question open for now.

Let’s run the numbers and compare to the table from before:

One of the things I like about this strategy is that it has a nice back story. We have to share the IL risk somehow, there’s no working around it. If ETH goes up in price, the ETH supplying side just made a lot of money — meaning they can bear the IL on themselves and keep a happy smile. If ETH goes down, the ETH supplying side is already in the red, so this is the time to share the pain. The added bonus for the USDC supplying side is that when this happens, they’re actually buying some ETH for a low price — and buying the dip has a great upside potential.

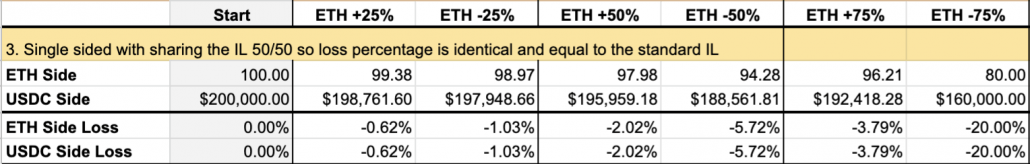

For completeness, let’s also present the numbers we get if we were to split IL equally between the two parties. The calculation is quite simple and has a very nice air of symmetry about it.

Back to our usual example.. On day 30, when the sides want to remove liquidity, ETH price is higher and is now $2500. When the LP tokens are burned, instead of the original 100 ETH and 200,000 USDC, we have 89.44 ETH and 223,606.80 USDC. Side A has a small loss over its principal of 100 ETH, and Side B has a small gain over its principal of 200,000 USDC. Can we find a number down the middle where both sides have the exact same loss over their principal?

The magic number is taking exactly 24,845.2 USDC and swapping it to ETH. This will give us 99.38 ETH and 198,761.60 USDC. This means both sides now share a slight loss. How slight? Exactly 0.62% over their initial principal investment. This 0.62% figure should be familiar — this is exactly the IL that we had earlier when doing standard double-sided farming.

Let’s run the numbers and compare to the tables above:

This strategy is very symmetrical and this is indeed quite elegant, but I have to say that personally I don’t like it. When doing single-sided farming, the two parties are never equal. Forcing symmetry, though elegant, is not necessarily a good thing.

The purpose of this post was to show how we can implement different strategies to share IL between two parties engaged in single-sided farming together. Each of these strategies may appeal to some and has advantages and disadvantages.

We’re not limited by these three alone. We can also mix them together and form interesting combinations, for example — take 50% of strategy 1 and 50% of strategy 3. So IL is not perfectly equal, but we do favor protecting the USDC side.

We haven’t mentioned the rewards when discussing these strategies either. If farming together yields 40% APY in SUSHI reward tokens, we still have an open question of how to divide the rewards between the parties. It makes sense to assume that if IL is not shared equally, so won’t the rewards. Naturally, the party exposed to more risk should also reap higher rewards.

If you’re curious about what we’re working on and don’t mind seeing work-in-progress that hasn’t been properly announced yet, feel free to follow us on Github:

···

Notes

This document details a project which is currently being researched by the Orbs team and ecosystem contributors. The project is currently in concept mode and is being portrayed herein as currently envisioned by the Orbs team.

Orbs is a decentralized project driven by community contribution and guidance. The product and functionality detailed in this document therefore constitute a mere proposal assembled from community feedback and are subject to change continuously as new requirements arrive. This document provides no guarantee that any offering, product or specific feature will become fully or partially developed.

The information contained in this document shall not form the basis of, or be relied upon in connection with, any offer or commitment whatsoever in any jurisdiction.

We use cookies to ensure that we give you the best experience on our website. By continuing to use our site, you accept our cookie policy.